In our nearly two decades in the plural community, we’ve come across a lot of self-help writing for multiples, but most of it is focused on trauma recovery or in-system communication rather than practical advice for daily life. Most plural systems don’t spend every minute recovering from trauma—we have full lives that include jobs, kids, bills, friends, family, pets, school, college and hobbies.

Unless they’re independently wealthy or receiving disability benefits, plural systems have to work for a living (after all, Thor still has to pay the bills)—and there are extra considerations for systems to take to succeed on the job. Living plural is a kind of personnel management in itself—you need to allocate staff, see how team members’ skills complement each other, communicate with each other, determine short- and long-term plans, and learn how to bring out the best in each system member. These personnel-management skills are common to most plural systems at work. That said, every system’s approach to work is different. In some groups, there are one or two system members who do all work tasks. Other systems, meanwhile, have no control over who is available to work, so they have a revolving door of members on the job. As for us, all six of our primary frontrunners go to work, but different people perform different tasks.

Though there are some differences, this list will also work for college/university students, since time management, task allocation and other workplace skills apply there, too.

Limitations: We work a traditional 9–5 job, though we’re also a self-employed consultant. We have an advanced degree (and a lot of student loan bills to prove it). Some of our advice about benefits and accommodations is US-centric, but the basic information should apply elsewhere, too.

Identify your strengths and weaknesses.

We have distinct strengths that can strengthen our work—as well as identifiable weaknesses that can show up when we’ve assigned the wrong system member to the task. At our best, we’re able to complement one another, just as an external group of colleagues would.

We recommend making a list of the headmates who go to work. These system members can go to work regularly or just participate occasionally. After you’ve done that, you can identify any of the strengths and weaknesses you or others have noticed on the job or elsewhere.

Identifying your strengths and weaknesses can help you allocate tasks and cover for each other if a system member is unavailable. It’s helpful if there’s some overlap between your system members’ skills—there usually is for us. For example, Jamie is a skilled editor who knows how to smooth out others’ writing quirks—for example, our tendency to use British spelling, Hess’s aversion to capitalisation, or Vova’s occasional Russian-flavoured turn of phrase. But Jamie isn’t the only good editor—Jack can also edit, and Zip can eliminate the use of Briticisms. Jack is good at typography and design, but so is Jamie. Yavari has an especial talent for research, but he’s not the only one; most of us can do it well.

Learn what internal mechanisms help or hurt your ability to work.

Individual strengths and weaknesses aren’t the only things that can affect systems’ ability to work effectively. Some groups have internal communication systems—control rooms, computer networks, meeting rooms—that help people make plans and divide tasks. Others may not have those systems and have to use external methods to communicate: they may use analogue or digital note-taking systems, they type messages to each other in a private chatroom or text file, they talk aloud, or they make voice recordings. We use both internal and external communication methods—talking in headspace, typing messages to each other and syncing them on iCloud to be used on all our devices, and talking aloud when we’re at home (it’s a good thing that our only housemate is our cat, at least for those purposes).

Some systems, like ours, have autopilot mechanisms that allow them to hide their plurality from the outside world. Thanks to our autopilot, system members’ accents and mannerisms are homogenised when we’re at work or in other spaces where we’re not openly multiple. Though there are some limitations—Jack’s accent is hard to hide, even with the filter running. He’s not usually a public spokesman, but he was forced to do it at an overwhelming temp job we had several years ago. His accent kept slipping through, and some people noticed it. Luckily, we had an outworld explanation to hand, so nobody pushed the matter—but it was still embarrassing.

(For more tips on system functioning, check out Jamie’s ‘Keeping It Together’.)

Use tools to help manage your work.

Everyone can benefit from having more tools in their arsenal to navigate the workplace, but those tools are especially helpful for disabled and neurodivergent people. Sometimes you’ll have to identify the tools that work for you through trial and error—I know we’ve had to. We’ve mentioned some of these before in the ‘internal mechanisms’ section, but we’ll go into more detail here.

Most of our tools are digital, mostly because we can sync them across our devices (personal laptop, work laptop, phone, tablet) and search for specific terms such as ‘meeting with boss’.

A note about digital tools: we use Apple products (MacBook, iPad, iPhone), but similar programs exist for Windows and Android. Some are completely free or have a free tier, but others are paid-for—we’ll mark those with a dollar sign. Subscription programs are marked with $S. We have a bias against subscription-based programs with one or two notable exceptions—we’re generally opposed to the practice of renting software indefinitely, since who needs digital landlords?

Digital management tools

- To-do and agenda apps. Our primary to-do app is Things 3 ($). We’ve also tried Agenda ($) and OmniFocus ($/$S). Cross-platform programs include Todoist and Notion.

- Writing and note-taking programs. The primary ones are Bean (Mac, free) and Quick Draft (Mac/iPhone, $). We’ve also used Google Docs (cross-platform, free) for this purpose, though we prefer desktop software to web apps. For writing projects (articles, stories and so on), we use Ulysses ($S).

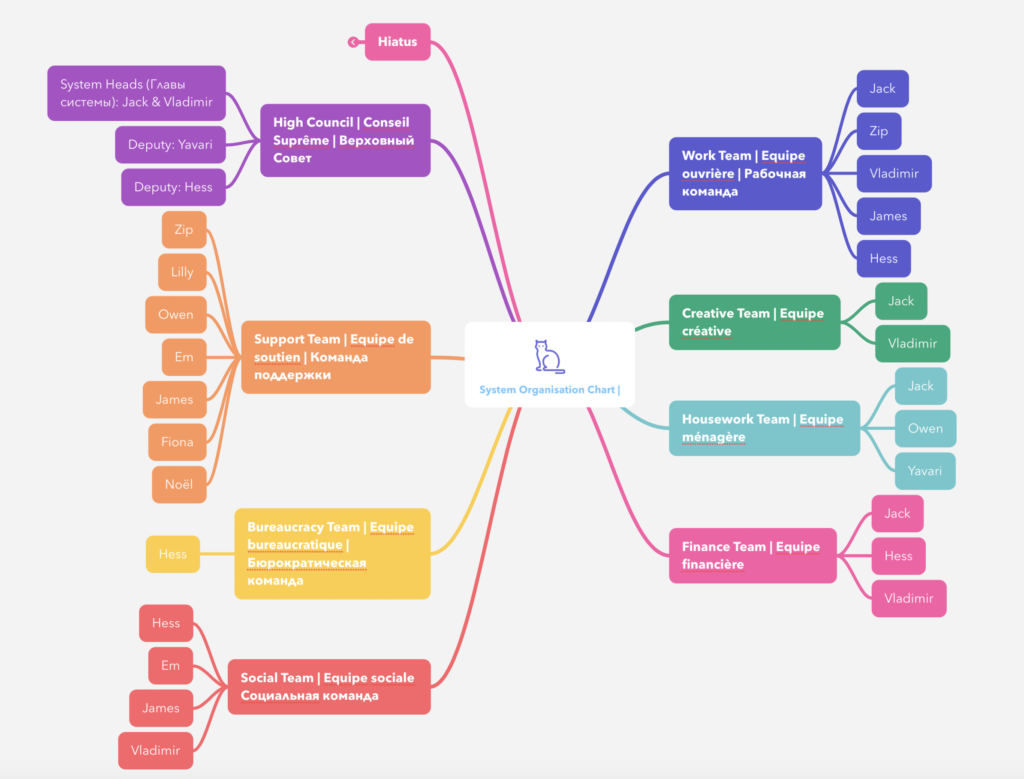

- Mind-mapping apps. For more visual-minded people, mind maps can help you identify roles and illustrate your system’s structure. We use MindNode ($S), but you can also try the free XMind or FreeMind, and some people have also used the multipurpose Canva for mind-mapping as well. If you’re really dedicated and patient, Adobe Illustrator ($S) will work too if you’re already using the program for work. One of our mind maps shows our system’s organisation chart, and the other is a flowchart for handling mental health crises.

- Project management software. We use Asana (cross-platform) at our job. We don’t have individual system members’ tasks managed, but it’s still a good tool to use with external teams.

- Spreadsheet and data management apps. It’s rare that we use spreadsheets for system organisation, but some people benefit. When we need spreadsheets, we usually use Apple’s Numbers or Google Sheets.

- Calendars. We mostly use the built-in Apple calendar, since we can have it sync across our devices. We have certain work tasks listed on it to make sure we get things done on time. It also works well with our Google and Outlook emails. For shared calendars, we use Google and Outlook.

Analogue management tools

We rely mostly on digital tools, but that doesn’t mean that pencil and paper are of no use to us—quite the opposite! When the power goes out or when you need to do something immediately, analogue tools are your friend. Here are the ones we’ve used and benefited from, as well as ones that help others.

- Dry-erase calendars. We’re much better with digital calendars, but these work for some people.

- Sticky/Post-it notes. These help us for brief reminders like ‘Meeting with So-and-So at 8 am’ or ‘Vova – start writing article’.

- Notebooks. Notebooks and sketchbooks are our favourite analogue tool by far. We prefer to get ones with high-quality paper (eg, Leuchtturm or Moleskine), since we use a lot of pens and markers that bleed. But you don’t need anything fancy for this—choose whatever whatever works for you and fits into your budget.

- Multicolour pens. Some companies make four-colour pens that you can associate with different system members when you write to each other.

Actively work with your boss, clients or colleagues to make your job more accessible.

Communicating clearly is an essential part of being successful in the workplace, but its importance increases when you need extra support.

Some people know what their needs are straight away—and these are the lucky ones. These are the ones who come armed with a list of strengths and weaknesses (or ‘growth areas’). They’ve got a stack of management and self-help books at the ready, and they know how to anticipate problems at work before they start. These seemingly lucky people are often those who have hit enough roadblocks at work that they know what to prepare for this time around. This isn’t us—we have a tendency of playing things by ear. We’re trying to get better at this, though.

Sometimes you’ll know it’s time to share your needs at work if someone has noticed erratic or flagging performance. Vova, who joined the system this year, had a hard time with a number of high-detail routine and repetitive tasks. (We all do, but they irritate Vova more than they do anyone else.) This difficulty was reflected in this year’s performance review. After talking to our boss about developing concrete ways to keep track of our work, we had an internal conversation about work assignments—and started looking for a new job, since we do better at conceptual and abstract work than menial grunt work that we’re only doing because we had to take a survival job after a mental health crisis. We’re using formal accommodations because a lot of ‘easy’, ‘low-skilled’ work is actually more difficult than conceptual work, which comes to us more readily.

Of course, you don’t need to tell the other people at work about individual system members’ struggles. In fact, we recommend against it unless you’re at an organisation that specialises in mental health and is actively trying to support people whose psychiatric conditions go beyond the ‘respectable’ duo of anxiety and depression. Instead, say that you are generally able to do the job but that you may need extra help with tasks that are challenging for a particular headmate, or if it’s a temporary issue with a misallocated system member, just say that you’ve been struggling temporarily and are ready to get better after you’ve reassigned your tasks.

Request formal accommodations if they’re available.

In many countries, including the United States, workers with disabilities have the right to seek formal accommodations at work. These accommodations can’t change the fundamental nature of the job (for example, if you’re a professional web designer, you can’t modify the structure of the job to eliminate the need to code in HTML and CSS), but they can help you perform those fundamental tasks with support. You may need to have a healthcare provider, such as a therapist, GP/primary care physician, psychiatrist or clinical social worker, write a letter or fill out some paperwork.

The Job Accommodation Network has examples of reasonable accommodations disabled people can ask for on the job. Although the legal information on the site refers to the Americans with Disabilities Act and other US-centric legislation, the specific accommodations it suggests (eg, job coaches, timers, software) apply to workers everywhere.

If you consider your multiplicity disabling, consider seeking a formal diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder (or a different condition if applicable, such as PTSD) and applying for benefits.

Some systems may not be able to keep a job for a number of reasons. Some multiples struggle to develop internal communication systems, and scheduling and planning may be impossible when everyone is working at cross purposes. Or another disability may be impeding their ability to work, even if the system has developed good communication methods. In these cases, we recommend seeking a formal diagnosis of DID (or another psychiatric diagnosis if applicable) and applying for benefits. It can take a long time to be approved for benefits, and you may be be turned down once or more if you apply. This is the case for benefits administered by the US Social Security Administration, including Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Income (SSDI). Many disabled people use lawyers to help them get SSI and SSDI because rejections are extremely common at the first stage. You may want to enlist the help of local disability organisations that specialise in supporting people with benefit applications.

—Vova Romanov, Jamie Dawkins, Yavari Caralize and Hess Sakal, 2023